I’ve read all kinds of manifestos, from the short to the Communist. I can either take them or leave them, honestly, which is probably why I haven’t come up with one of my own. They can be motivating or distracting, boring or fascinating. I can nod in agreement with every word or wish that the words could be scrubbed from the page before my eyes. Which is why I’m not completely surprised that I didn’t find Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art to be the motivational masterpiece that so many others have.

I’ve been waging my own war with waning creativity lately, and perhaps that’s my problem. For Pressfield, “resistance” is the enemy: the writer’s block, the tardy muse, the drugs and the sex and the rock ‘n’ roll that’s so much more appealing than forcing words to appear upon a page. I can’t say he’s not right. If there ever was an enemy to creativity, it would be that unnamed force that keeps the muse at bay. All I know is that war is exhausting.

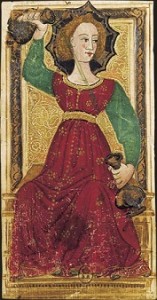

Raise that keyboard high! Let the pencil strokes fly!

So, we fight! We lift keyboard in hand and raise our pens to the fore! We heft that palette upon our shield-arm, and thrust our brushes forward. We slice and dice our ineffable enemy with keypresses and brushstrokes. It won’t ever stop. It’s around us everywhere, both seductive and violent. It seeks to distract us from our objective: getting words on the page, lines and circles on the canvas. It will stop at nothing to stop us.

You think you’re safe, don’t you? You’re ensconced in your office or your studio, staring at the wide wall of your monitor, of your canvas. You’ve barricaded the door, and blocked off all extraneous thought. You have fingers poised, ready to perform intricate actions, to bring the vision that dances behind your eyes to life before you. You ready yourself. You’ve made sure your Maginot Line is well-fortified, and you’ve allied yourself with your neighboring distractions.

How about a little cake? something whispers in one ear.

You look around in alarm. Nope, there’s nothing. No one is holding a delicious slice of indulgence over your shoulder just inside your peripheral vision. You return your attention to the blank whiteness before you. You set your fingers on the home row. You dip your brush into some basic black, then blue, and start stirring.

You’ll never be able to bring it to life, the voice says, menacing now. You think you’re good enough, but you’re not!

But I am! The voice is defiant, and you press deliberately upon the shift key. The brush feels heavy in your hand as it hovers above the canvas. And if I’m not, who will bring my creation to life?

That’s right! Just hit that key! I dare you! And then another. And then you’ll have a whole string of nonsense to cringe at! Better to back away.

But! But! You slam your fingers over the keys now. You’ve managed to write a sentence. Your first line isn’t a thing of beauty, all smudged with paint or faulty antialiasing, but it’s there. It’s a start. You can always fix it later.

And I’ll be here later to bug you! the voice says.

You think you’ve won a respite, but Resistance has breached your Maginot Line. Suddenly that imagined cake is looking pretty good, except it isn’t with you. It’s at the bakery, halfway across town. You put down another sentence, stroke out a gentle curve. You mix another color, and futz with italics. The cake screams, Buy me! Its voice is louder than mere resistance.

Suddenly, you’re exhausted. You’ve scratched out a start, but it isn’t anything close to what you intended, and your defenses are down. You should keep slapping away at the enemy with your keyboard, jabbing at it with the cruel ballpoint of your trusty pen. Instead, your head dips.

Curse you, Resistance! You’ve won!

I’ve never been a warrior, unlike Pressfield. I just don’t have the will to fight every day of my existence. He might have armor and an unflagging spirit. His words drip with challenge, and have been honed to optimal sharpness by a master blacksmith. He slays, he declares victory every day. I try to slay, thinking of the page’s blankness as an enemy, but instead I shrink away, pained. I’m slashed to ribbons even as I’m seduced by distraction.

My inner storyteller is battered and bleeding, and she seeks respite from his relentless words.

And now she’s rambling about the Storyteller… sigh.

My inner writer isn’t a warrior. My muse isn’t Durga. Instead, she’s insatiably curious. She’s innovative in her own quiet way. She wants to know as much as you do what lies ahead for the myriad characters she’s woven, and wants to spin a yarn as best she can as they interact in the world she’s sculpted. She is Storyteller, both for herself, and for anyone else who cares to listen to her words. She hears Pressfield’s stirring words and lies down for a nap.

Nope, not for me, this endless clash! It hurts too much! Just tell me what comes next!

What next? What is next? She reaches inside herself for the world she’s created from the soil of thought and reality. She feels it take shape in her hands as she feels the silken strand vibrate that she keeps connected to her characters at all times. She sees as they do, and feels the clay flow into buildings, trees, races. She watches and listens as they speak to each other. She smiles as they become all the more alive in interaction. In life.

Tell me, she whispers to them, what are you going to do?

Sometimes they comply with what she’s envisioned. Sometimes they don’t, and chart their own course. She is the last to predict, the first to step aside and let them assume control. She speaks their words and thoughts. She reveals their motivations and describes their actions. She allows them to guide her fingers over the new world she’s created and refine it. She is their conduit, their channel, and when they rest at the end of their journeys, she weeps until a new world beckons or new characters introduce themselves.

What’s next?

That should be my rallying cry, but sometimes I know what comes next and my Storyteller balks. Why should I tell the story? I already know what happens. Who cares?

Because writing isn’t always about you, I tell her, but she usually ignores me.

I tell her to put on her armor and poke and prod herself into compliance with the corner of my keyboard, but she just curls up in a ball and hides. I can’t blame her.

What does that have to do with archetypes?

I just recently started on Archetypes: Who Are You? by Caroline Myss. So far, I’m not finding anything particularly surprising about it, though I haven’t really spent much time delving into my primary archetypes to see if there’s anything I can use to get me up off my butt creatively.

Myss points out in her introductory chapter that archetypes are universal. Months before I picked up the book, I’d already intuited that Pressfield’s creativity is best represented by the Warrior archetype and that mine really isn’t. I’m not a warrior, dammit! I’m a Storyteller! When I took Myss’ test at archetypeme.com, the results didn’t surprise me so much as finding out one of my dominant archetype’s alternate names is “Storyteller.”

In case you’re curious, my dominant results were: 33% Creative, 33% Intellectual and 14% Visionary.

I can see why so many creative and innovative artists find Pressfield’s work so motivating: my guess is that they either have a hint of the Warrior or the warrior’s drive within them. Pioneers, heroes, and advocates all have to harness the warrior’s courage to impel others to change. I’m a little too laid back (a very kind way of saying “low energy”) for his words to spur me properly. Instead, I just felt tired after reading The War of Art.

The importance of ritual

If you take a look at the Amazon reviews for Pressfield’s book, you’ll see a number of comments about how Book 3 goes off the deep end in speaking of angels and rituals to the muses. Sadly enough, this was the part of the book I found the most personally applicable, even if the language was highly figurative and “mystical” in nature. Maybe Pressfield’s dead serious in viewing his language as concrete and literal, but I resonated with it on a more abstract level.

I’m going to diverge for a couple of seconds into the land of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and cognitive functions. You may or may not see the sixteen types of the MBTI as more pseudoscience and inaccurate mumbo-jumbo (I’m mixed about its true accuracy, even if I find my “type” describes me almost perfeclty). Either way, to a certain extent, I’ve found the side-theory of cognitive functions to be very helpful in understanding how my personal thought process works. Essentially, in this theory, there are four primary functions, expanded to eight based on their inward or outward direction: Thinking, Feeling, Sensing and Intuition. All of these four can either be Extraverted (outwardly focused) or Introverted (inwardly focused). I’m using Jung’s spelling of “extrovert.”

My personality type is INTP (Introverted Intuitive Thinking Perceiving), and my cognitive process stack is as follows:

- Dominant: Introverted Thinking (personal inner mental model of the world outside)

- Auxiliary: Extraverted Intuition (awareness of outer patterns and the complexity of the exterior universe and all its possibilities. The “wheeeeee!” in life)

- Tertiary: Introverted Sensing (recollection of personal experience in all its details, awareness of how the body feels internally)

- Inferior: Extraverted Feeling (longing for universal harmony, universal values, the welfare of all within a group)

If you read a lot of books on developing intuition, you’ll find that most encompass the development of introverted intuition. This is the land of gut feelings, your “sixth sense,” and the universe within you. Pressfield’s was the first I’ve ever seen that explains exactly what extraverted intuition feels like. You look and scan everything around you to get the gist of reality. Suddenly, you’re smacked with an “A-ha!” moment, which can either hit you like a brick in the face, or like a gentle whisper. When you hear of “angels” or muses actually whispering an idea in someone’s ear and you secretly wonder if the purveyor of such words is actually bonkers, maybe they aren’t. Maybe they’re hearing their Extraverted Intuition talking and expressing the sensation in the most accurate way they can. The experience feels highly abstracted, so the language follows suit. Or maybe they really do believe they’re hearing angels and they’re nuts.

Pressfield’s rituals are precise, and his language, frankly, sounds insane if you’re not comfortable with extraverted intuition. He’s elaborate in his processes for preparing his perception for the act of writing. My own processes and rituals are far less precise, wacky and intense. But, really, to ensure my best writing I do have a ritual to prep my mind for the writing act. In short, I prime my perception just as Pressfield does with his muse-invocations and prayers.

Basically, I imagine what mood I’m going to try to convey for the writing session. I then visually scan my hard drive for the album that I think conveys the mood the most accurately. I take a few deep breaths, fire up the album on Windows Media Player, and then I open my document. Then I close my eyes and try to tap into my characters’ inner logic and emotions. I remember what I wrote the previous session, and let myself get sucked into their world. Without that kind of initial ritual and initiating process, my writing and inspiration suffer.

A germ of what might work for future exploration…

Who is your inner writer? Who is your outer persona? Are you a warrior? A hero? Someone who loves to slay inner demons?

If you’re like Pressfield at all, this manifesto will get your blood pumping.

I’m not. Instead, I’m thinking I need to find a way to spark my Storyteller’s curiosity to get moving again. I need to tap into her need to tell the story to others. I need to actually perform my rituals to get her interested again. In short, I need to focus on priming my perception.